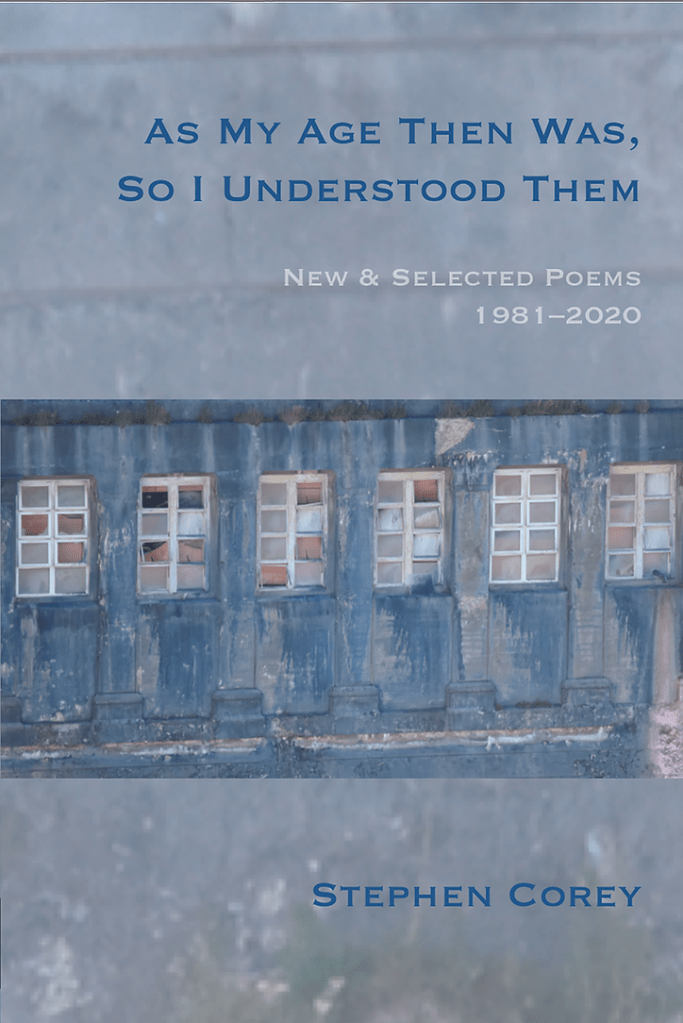

This review was first published in James Dickey Review, Vol. 38, 2022

During his decades-long career as a poet, teacher, and editor, Stephen Corey has surely been exposed to a wide variety of styles, forms, tones, and genres from a multitude of writers and poets. Yet, he continues to write in his own distinct and original voice. At times sentimental, often irreverent, Corey guides the reader from the familiar into the unexpected and effortlessly transitioning to the uncomfortable yet with the support of a father’s hand as if to say, “See, this is what the world is really like,” just before bringing the reader back to a warm embrace.

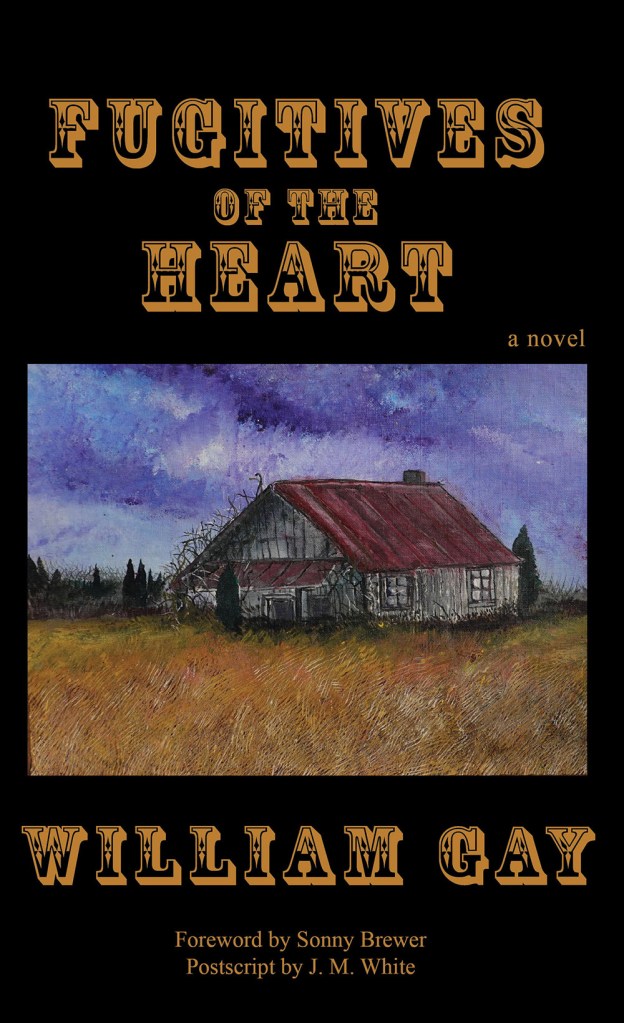

In his latest collection, As My Age Then Was, So I Understand Them, Corey supplements poems gleaned from some of his previous publications with a set of new, uncollected pieces to create a 40-year retrospective of the artist’s work. However, this collection is more than just a collection of greatest hits, more cohesive than a “Portable Corey.” By reaching back to different time periods in his life, Corey reveals to the reader what was important to him at particular points in his life. The poems are arranged mostly in ascending chronological order with the exception that the newer poems appear first. And although it is interesting to compare the progression of his craftsmanship through the years, it is equally impressive to note that these poems, in their entirety, just seem to belong together as one cohesive compendium. The publication dates serve more as a key to background and prospective rather than a progression to mastery. Yes, there are differences between the early and later works, but the quality is there from the beginning and does not ebb.

The perpetual student will find empathy and understanding in many of these poems. In “What We Did That Year, and the Next,” the process of breaking in books in order to read them is used as a metaphor for preparing fifth-grade students to learn “…in the words that wouldn’t stop / if only we kept on opening.” In “Freshman Lit & Comp,” a professor is underwhelmed by a young blue-collar man who seems to have little interest in studying the literary masters until he discovers Homer’s descriptions of Hephaestus, Greek god and patron to those who toil.

Striving for perfection and beauty with the knowledge that we, the artist, will never quite get there is the theme of “New Delight.” Despite this comprehension, the artist eventually learns that the beauty truly exists in the very act of endeavoring as we create “The poem, painting, song–the golden ring / we miss and miss, our arms too short although we lean. / The botched creation holds the vital thing.” In another poem, “The World’s Largest Poet Visits Rural Idaho,” Corey addresses the conundrum of why artists continue to ply their craft oftentimes in the face of unbelievable sacrifice and why we feel the drive to continue our work. Because it has to be done in order for one to come to terms with oneself, and sometimes simply “…because the battered humming / in his head will not stop.”

The collection also serves as a love letter to Corey’s art and the artists who influenced him. Emily Dickenson makes a few appearances: one as an apparition in “The Ghost of Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) at the Kroger Gas Station;” another in “Called Forward,” a dual eulogy for both Dickinson and Corey’s father who lived almost exactly a century apart; and “Emily Dickinson Considers Basketball,” an ode to the sport in the style of the master. Even when his tongue is firmly planted in cheek, Corey adroitly honors his mentors and those who have deeply influenced him. He dedicates an entire section of some of his newest work entitled “Learning from Shakespeare.” And in a poem written earlier in his career, “Understanding King Lear,” the poet stirs a container of yogurt while pondering the Bard’s everyday life inviting the reader to “imagine / Shakespeare’s life, / the daily incidents, / the human brilliance.”

This famous Howl I hold is worlds

these women/girls will likely never know—

world of ecstatic suffering,

world of suffering made ecstatic art—

for they are not bound toward impoverished dissolution,

nor likely to follow their father

on his voyeur’s journey through the text

toward many worlds he will likely never know.

Yet here they are, showing there is no limit

to what might align in the total animal soup of time.

As above, some of the most endearing poems in the collection are the ones dedicated to Corey’s children. “Learning to Make Maps” begins with his seven-year-old daughter drawing a map to her friend’s house for her father to follow later when he goes to pick her up. The dad reflects on his own childhood and the image of his own father and tells his daughter, “I will be there when you finish / I promise this map will do.” The poem, “My Daughter Playing Beethoven on My Chest,” reflects on a scene where a nine-year-old girl “on the absolute edge / between her dying childhood and / that confusing ecstasy to come…” plays invisible piano keys with her fingers on his chest: “Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ thrummed above my lungs / as if she were typing out a secret/ well-known message.” The father acknowledges that although he is unable to play music as well as his young daughter, he certainly “had ear enough to follow / the lead of her growing fingers—”

In “To My Daughters at My Death,” the poet contemplates his own death as he addresses his daughters for what he imagines will be the final time, and he pleads, “where have we left ourselves now that we’re possessed / by the separate worlds we’d only feared or ignored, / now that I have no hand to touch your hands?” Corey seems to be very conscious of how his own eventual death will affect his children, and this theme of mournful inheritance is revisited in other pieces such as “Editing Poems During a Hospital Deathwatch” where an editor tries to work while his mother-in-law slowly dies, or in “The First,” a sentimental poem about the death of a first lover.

Corey takes a deeper dive in reflecting on former lives in “Divorce,” a poem about a man who attends his ex-wife’s funeral. Accompanied by their grown daughters, he silently addresses the deceased, “As ever, I don’t know how to leave—/ which last words to blurt across this mound, / which woman to clutch as I turn, / which wrong choice to make once more.” Then in “Spreading My Father’s Ashes,” the poet reflects on his troublesome relationship with his father as he is asked to fulfil one final request where “Dropping becomes throwing / as the path circles back to the cabin, / the circuit of the land / more finished than the task. / I aim for things, but miss. / A wind-shift fires one throwing / straight back in my face.”

The poems in this collection are thoughtfully entertaining. They are, at the same time, both literary and playful, sentimental and mischievous, heartfelt and erotic. There is much to absorb for the poetry enthusiast and the practicing artist. In Corey’s poems, every word counts. The style and rhythm of the lines work together in an almost natural way to either emphasize or lay bare the metaphor and meaning for which each poem reaches. Corey challenges the reader and, especially fellow poets, to treat the subject matter and the emotion respectfully while not taking themselves too seriously. It is refreshing to see how proudly a writer gives tribute to those who have influenced him, even more so when that writer himself has influenced so many.